A Chinese Character Yuan (缘) Unfolds His 3D Life In China

Episode 1:

By Manling, China Plus Host

My guest today is David Moser, the Associate Dean of Yenching Academy at Peking University. Many people know him because he often appears on TV and radio to comment on China and international affairs. But perhaps fewer people, especially members of the younger generation, would know that this American scholar used to enjoy celebrity status in China as a crosstalk comedian and jazz musician.

Episode 2:

To this day, people still compare him with Dashan, the Canadian performing artist and for a time the most famous waiguoren (foreigner) in China. To prepare for an interview with such a larger-than-life personality, I decided to dig into his past in order to get a better picture of him today.

You can also find the shows on Apple Podcasts.

David Moser became a household name in China overnight after he and three other performers from overseas performed a crosstalk comic skit in the CCTV Spring Festival Gala on the Chinese New Year's Eve in 1999.

Episode 3:

The gala is a grand performance, and for many, many years it has been customary for Chinese people to watch it at home with their family as they wait for the arrival of the New Year during Spring Festival. Watching a video of their performance 20 years later, I still found myself entertained by these waiguoren cracking jokes about their lives in China in a rather awkward Chinese dialogue. Looking at that same man in front of me today, I realized that during the past 20 years David had undergone a "face transition" (how David described China's changes) no less dramatic than the one that China has gone through that he was here to witness. He has transformed himself from a celebrity into an expert on China studies by following the beat and rhythm of the country's reform and development.

When I asked what brought him to China, David replied: "It's yuan" (缘). His answer caught me off guard. Yuan (缘) is something of a nightmare for translators regardless of their age or experience. Because it lacks an exact equivalent in English, translators usually give up looking for a particular word to match it and digress in an effort to explain its meaning. Also known as yuanfen (缘分), at its core it means the fate, destiny, divine intervention, karma, chemistry, or even luck that brings people together. It can describe a happy relationship between a man and a woman, or the inevitability of good things happening to good people. David's story was an example of how a single Chinese character can define a man's relationship with China.

The Chinese Tongue Twister

When he was still in high school, David met a Japanese woman. Hearing her speak sparked an acute interest in this alien language, and he found himself wondering what phonetic ideas and pictures appeared in her mind when she was uttering those strange sounds. It awoke within him a curiosity in foreign languages that was stimulated further by a visit from two homestay Chinese students from Taiwan, which fanned this flame into an enthusiasm for learning Chinese.

Instead of starting him off with something simple like hello ("Ni hao! 你好!") the first line he learned was a tongue twister: "吃葡萄不吐葡萄皮" (chi pu tao bu tu bu tao pi). It's the Chinese equivalent to "She sells sea shells on the seashore," which is used to train (and torture) English majors at universities in China. Tongue twisters are fun and David was a fun lover, so naturally he got hooked on one of the world's most challenging languages and embarked on his lifelong journey of becoming a Chinese linguist and expert. With the encounter of the Japanese lady and the students from Taiwan, he was led to China. That is yuan (缘).

The Holy Grail Book of Practicality

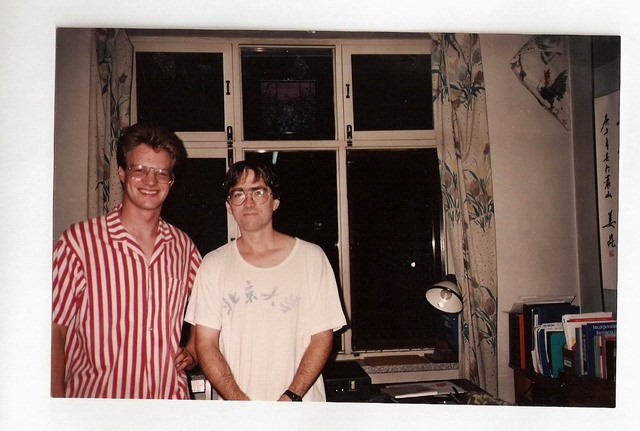

There is a saying in English that "misfortunes don't come alone". David's good fortune when he first came to China suggests that maybe good luck doesn't arrive alone either. In 1987, while he was a student of music at Michigan University, his limited self-taught Chinese got him a job as a visiting scholar at the prestigious Peking University in China.

He joined a team chosen to translate Douglas R. Hofstadter's Pulitzer Prize winner book "Godel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid" into Chinese. This was a formidable task: the book, which brings together concepts of music, painting, philosophy, math, physics, and artificial intelligence, was something of a Holy Grail for Chinese people searching around for a tool to better understand the outside world.

David described the translation process as a hellish experience. He worked on-and-off on the project for more than four years as he shuttled between the United States and China. The silver lining of this dreadful job was that it prompted him to apply to the University of Michigan's Master's and PhD programs to study Chinese linguistics and philosophy, so that he could cram in as much knowledge about the language as he could in order to finish translating the book. In the end, the efforts of David and the team paid off, and the Chinese version of the book remains a highly sought-after text for professionals and intellectuals. That a recommendation from his teacher landed him the translation job, which was to push his life in a new direction, is a prime example of yuan (缘) in action.

Xiangsheng or Crosstalk

During his stay in China, David picked another extraordinarily difficult task for himself: learning crosstalk, called xiangsheng in Chinese. There are similarities between crosstalk and Western stand-up comedy. Both involve on-stage banter and cracking witty (and oftentimes dirty) jokes. Crosstalk differs from stand-up in that it is less spontaneous or improvisational. Western stand-up comedians usually start by developing their own style of humor and presentation, whereas xiangsheng performers study the craft as apprentices by starting with the rich collection of classic arias. David and I both agreed that if xiangsheng performance is like writing a formal essay, stand-up is like stream of consciousness writing.

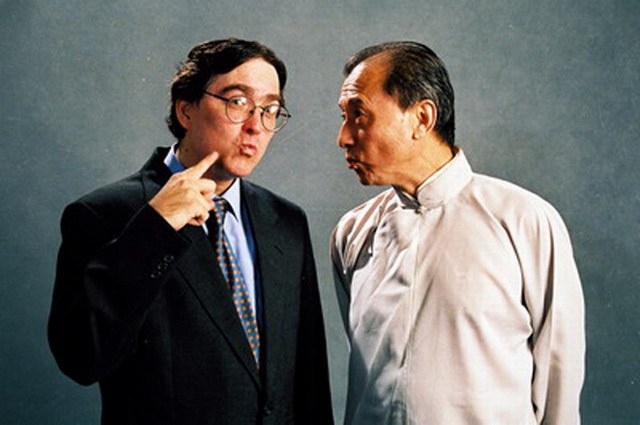

David became a disciple of the xiangsheng master Ding Guangquan. When asked why he decided to learn xiangsheng, he said it was because he found Chinese textbooks to be mind-numbingly boring. Humor is perhaps the most formidable challenge for learning a foreign language, and it was by practicing crosstalk that David could learn traditional Chinese stage acting along with the Chinese language , culture, history and philosophy all-in-one.

David joined hands with some of China's most famous pop musicians such as Cui Jian and Bian Liunian. Meeting stars like these helped elevate him to celebrity status and he became a household name in 1999. These fortuitous encounters are another example of the meaning of yuan (缘).

The Perfect Yuan (缘) of Marriage

Yuan (缘) is not considered perfect without romance. David's story wouldn't be complete without a love story, and his provides a tale of how Chinese and American partners can come to understand and handle a romantic relationship.

After dating for a while, this typically passionate young American lad felt that his girlfriend was too cool and composed for him, and believed that they were slipping towards the brink of a breakup. His girlfriend, who would later become his wife, assured him that "the night was still young" and the best was yet to come. Her bright hopes for their future were a shock to David, albeit a very pleasant one, as he was so certain that things were doing downhill. These early days far behind them, they're now happily married with a daughter.

How was it that two people with such starkly opposing understandings about their feelings for each other come to remain in each other's lives? Chinese people might say it's a case of "有缘千里来相会" - no matter how far we are apart, we are destined to meet each other. This is a perfect example of yuan (缘) in a marriage.

His yuan (缘) with China Continues

It has been three decades since David Moser first set foot in China. He is now busily juggling three big jobs. As the Associate Dean of Yenching Academy at Peking University, he makes sure that the academy recruits the brightest young minds interested in China studies, and works hard at ensuring that they get the best possible education on this broad and complex subject. In this role, he calls himself a bridge between China and the rest of the world. Being an expert on China and international affairs, he shares his insights and observations about China with a wide range of people. And as a linguist he teaches and writes books about China and Chinese language.

As the interview drew to a close, it felt like I could almost see David's yuan (缘) with China gradually unfolding in front of me, and I felt certain that it was set to continue. As it happens, "unfolding" was the word David would use to describe how he had been mesmerized by a sense of China's positive uncertainties. David shared with me how a foreinger once used the word "romantic" to describe his feelings towards China. This resonated with him, just as his words resonated with me when he used the concept of yuan (缘) to describe his own experience. "Evocative" was the word David used to describe his feelings towards China. For some, China is like a mysterious and evocative lover who never stops offering new challenges to its pursuers. David described China as a land of hope and opportunities, and also of optimism, and he was fascinated to see how it gradually unveiled its charms.

I could feel David's pride in being not only a witness but also a participant in the nation's history. From a music student to a Chinese language learner, a visiting translator to a university lecturer, a celebrity on a national stage to a husband and a father, and from a linguist to an internationally–recognized China hand, David's life has been one marked by many stages of new growth.

David Moser loves China because it provides something he can't live without: boundless intellectual stimulation. This helps to explain why in his current stage of life he is even more of an intellectual than he has been in the past. I've come to realize that his yuan (缘) encapsulates a lifelong yearning for the profound depth and complexity of Chinese language, art, culture, and philosophy. And it's a yearning that I found deeply moving to witness. His bond with China, his future yuan (缘), is surely an unshakeable certainty. David Moser is on a path that will see him not only witness but actively take part in the creation of China's history to come.